We’re all having to run local area networks (LANs) these days. Back in the last century, our IT life tended to be based around our PC. Or maybe a pair of PCs, with the odd items of data initially being swapped between them via floppy disks. Techies call this Sneakernet.

As the century wore to a close, we started joining our devices together. At first, using wire—Ethernet cable. But by the time laptops became ubiquitous, our preferred connection between our devices used one or more wireless access points (APs), one of which would be a router, the connection out into the Internet.

Wired or wireless, the domestic backbone behind all this is the LAN. And when you have a LAN, it starts making a lot of sense to develop some kind of central repository for your data so that all your devices, PCs, media players, smartphones or whatever, can all have access to it. With, of course, an appropriate security structure.

It’s hard drive storage that’s not embedded in any one user device, or connected to any individual machine by cable. It’s storage attached to the network in general. With lucidity rare in the canon of industry jargon, it’s simply called Network Attached Storage, or NAS.

The art of the NAS can be complicated. And expensive. But the Synology DS119j is a simple, easy and economical introduction.

The DS119j, Plain and Simple

LET’S START BY UNPICKING the name. “DS” is because this is part of Synology’s Disk Station range of hardware. The “1” that follows indicates that it’s a single-drive NAS. The “19” is a bit of a puzzle; this NAS immediately supercedes the DS115j but isn’t to be confused with the DS118, which has four times the memory and a more powerful processor.

The terminal “j” is the big differentiator here. It stands for “Junior”, a reminder that we are on the nursery slopes with this one.

The DS119j—I’ll refer to it as “Junior” from time to time—is about as uncomplicated as any NAS could be. It comes as a plain chassis with no hard drive—you’ll need an extra purchase to make this work.

The drive used in this review (kindly supplied, like the DS119j itself, as a combined marketing initiative by Seagate and Synology), is a 4 terabyte Seagate IronWolf. Assembling these into a complete workable unit is simple. The two halves of the chassis slide apart, exposing its innards and the hard drive is then fitted directly into a plug on the chassis. Slide the chassis back together again, plug in the external power supply and the box is ready to report for duty.

That quick and dirty assembly does work, but Synology would rather you employ the machine screws it provides: four to hold the hard drive permanently in place and two to secure the chassis.

At this stage, the DS119j has no operating system. Just a bootloader that includes a Web server and means of acquiring a valid IP address that will connect itself to your LAN. The next step is to find the NAS’s web server from the browser of your client computer.

At this stage, the DS119j has no operating system. Just a bootloader that includes a Web server and means of acquiring a valid IP address that will connect itself to your LAN. The next step is to find the NAS’s web server from the browser of your client computer.

If you know how to read your router’s DHCP allocation table you should be able to track down that address easily. If you have no idea what a DHCP allocation table is, don’t worry. Synology has you covered.

Synology Assistant is a desktop utility available for Windows, the Mac and Ubuntu Linux. It seeks out Synology NASs on your LAN and then helps you install the operating system, DSM, by pointing you to Synology’s Download Centre.

But you may not need the Assistant. Type the “find.synology.com” URL into any Web browser on your LAN and you should see the Synology connection screen.

Synology Assistant

The Status LED turns yellow during memory testing.

Synology Assistant claims several advantages over that simple Find URL. It apparently offers to set up connections between your NAS and whatever printers you have on your LAN. It can also map the NAS as a drive letter under Windows File Explorer. You can use it remotely to test the memory of your NAS. This will reboot it into a temporary state that makes it inaccessible over the network.

Optionally, too, you can use Synology Assistant to trigger Wake on Lan. More of that later.

The printer story was a puzzle. We have three network printers here at Tested Technology Towers, and these all show up in File Explorer. Despite several attempts, Synology Assistant failed to detect any of them.

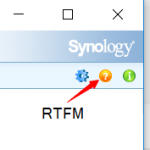

It turned out there was a very good reason for this. It’s known among technicians as RTFM (Read the F***ing Manual). Synology Assistant comes with a very comprehensive help page, accessed by clicking the yellow question mark in the top right corner.

It turned out there was a very good reason for this. It’s known among technicians as RTFM (Read the F***ing Manual). Synology Assistant comes with a very comprehensive help page, accessed by clicking the yellow question mark in the top right corner.

This useful guide would have saved me a lot of trouble if I’d read it earlier. It turns out that Synology Assistant is offering central management, not of printers scattered across the LAN, but of any printers you might have USB-attached to the NAS itself. I had none, so none were found!

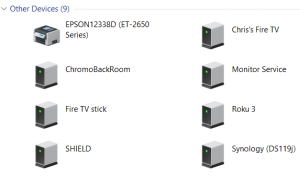

The DS119j shows up among “Other Devices” and can’t be added to Windows Explorer as regular network attached storage.

Drive Mapping

The drive mapping proposition was a more serious puzzle. You would expect to be able to log into the NAS from within Windows’ File Explorer, with its files then becoming immediately available thanks to what Windows calls “Network Discovery”. But with network discovery switched on (in Advance Sharing Settings) our Junior failed to make an automatic appearance.

Yes, it’s there under “Other Devices”, which means if you click on it you’ll bring up a browser with a link to its internal Web page. File Explorer is declining to acknowledge Junior as a legitimate Windows file repository.

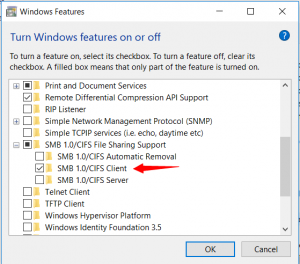

Type “Control Panel” into the Task Bar’s Search Box, find your way from there into Programs and Features and then choose Turn Windows Features on or off. You’ll now find yourself inside a list of Windows’ more arcane internal options. The picture shows you the setting to turn on SMBv1 client features.

At long last I found one that works for my Window 10 Home version 1803. Windows being Windows, of course, there’s no guarantee that it will work for other versions.

The DS119j Hardware

Built around an ARM-based processor (the same kind as used in most smartphones) and operating with what today is close to the lower useable limit of random access memory (RAM) size, this is a NAS designed to save on power consumption. And on capital outlay. Synology describes this as “affordable” and “budget-friendly”.

It’s tempting to pursue this comparison with a phone. A typical flagship smartphone would be driven by an eight-core ARM chip, each core behaving like an individual processor at speeds averaging around 2GHz. With either 6 or 8 gigabytes of RAM for its applications to run in, the phone could be expected to operate for a whole day on a 4,000 milliamp-hour battery.

To be fair, the DS119j costs only a quarter of the price of one of those phones. And this minimal configuration certainly helps the device run economically. But it hugely limits what you can do with it.

Power in Perspective

As NASes go, 5 watts idling and 10 watts working isn’t at all greedy. The QNAP TS-451 eats about 15 watts when standing by and 31 watts with all four drives rolling. Three times the wattage. The Junior seems to be just sipping the juice.

But having introduced the comparison to a notional flagship smartphone, I thought it would be interesting to do some back-of-the-envelope power-related calculations. Let’s consider an 8-hour working day.

Over those 8 hours our Junior, with its disk constantly churning (worst case, but let’s say), has consumed 10 x 8 watt-hours. That’s 80 watt-hours. A watt-hour is a measure of power, a quantity of energy stored or created. (Sometimes it’s more convenient to think of watts as watt-hours per hour.)

Assume that (like the NAS) I’m using this phone pretty well flat out all day and that battery just about gets me through eight hours. Working all day (or, perhaps, watching YouTube), my phone has eaten through 14 watt-hours of energy.

So our juice-sipping Junior turns out to be devouring almost six times the power of the smartphone. You might object that a NAS never runs flat out like that. (A phone occasionally may.) All right, let’s allow the Junior to idle through all those 8 hours. That’s still 40 watt-hours, nearly three times the consumption of our non-stop phone.

Sleeping Princess Mode

Which leads us seamlessly into the fairytale part of the DS119j story. Because Junior, like many other well-bred NASes, has a trick up its sleeve that recalls the world of the Brothers Grimm.

Like the Princess in the story, the DS119j can fall into a deep sleep for a hundred years. And be awakened by the kiss of a handsome Prince. Metaphorically.

Of course, the hundred years is any arbitrary period during which you’re not going to need an immediate response from your NAS. This isn’t just hibernating the drive and chugging along at 5 watts. In this deep sleep mode, Junior is only drinking enough juice to keep its Ethernet port awake. Effectively, it’s dead to the world, responsive only to that Prince’s kiss, a signal sent around to every device on the LAN, but addressed specifically and only to the NAS.

As you’ll have guessed, it’s not technically called a “Prince’s kiss”. But the boffins like to keep it in the fairyland domain: the official name for it is “magic packet”. And the process is Wake on LAN, or WoL.

There’s one other annoying catch you’ll discover if you’re running Synology Assistant from a laptop or trying to access Junior from your phone. The magic packet is a hard-wired Ethernet feature and won’t work over WiFi.

One solution would be to have a relay device hardwired to the LAN that you could access wirelessly with a command to sent the magic packet. As luck would have it, just such a device is already installed here at Tested Technology. It turns out that the designers of the FingBox had exactly this problem in mind. With the Fing app on my Android phone I can trigger a command that persuades the FingBox to send the magic packet winging round the wires.

More to Come

It turns out that there’s a lot more to be said about Junior than I was expecting. In Part 2 of this review, we’ll try to define the limitations of this device, cheered up by an optimistic view of the opportunities it opens up. I’m also hoping to follow up that power investigation with some practical tests

Chris Bidmead